I haven't done a weekend climbing post for yonks, so here goes. Hope I'm not rusty.

Whilst Finland has the right climate for ice climbing, it lacks somewhat in the geography. Yes, we have cliffs, but they're not terribly big. Last week, a friend in Norway was putting pics on Facebook of 300 mtr long WI3+s a short drive from where he lives. I was more than a little jealous. 30 mtrs is pretty huge round these parts. Nevertheless, there are some advantages to this geologic state of affairs, the lack of necessity of the '

alpine start' being prime amongst them.

Joel strikes me as a civilised chap on many levels, a polymath equally at home discussing engineering, ballet or the minutiae of the recent Israeli Knesset elections. But also, it appears, not overly keen on getting up too early - perhaps another form of civility in itself. So we didn't leave the metropolis until after 10 am. It could have been earlier but my slightly OCD-influenced approach to packing for an overnight camp meant I wasn't 'quite' ready when J. appeared at my door. Nevertheless, we motored eastward under blue skies and with a bright sun shining on white landscape. Stop one was at the ABC just east of Porvoo, a service station where I have eaten many a donut and supped many a coffee whilst on my way to sunny days at

Haukkakallio, summers past. So I had a donut while J. went for the full on lunch buffet, plate piled high with meatballs, potatoes, veg and salad - a theme that we will return to.

Sated, we turned northwards and were soon approaching our goal. I had recently seen

some fine pics of an icefall on a Finnish climbing blog and had mailed asking if the venue was public or not. Kindly, I was quickly sent the coordinates for the crag. Nearly a decade ago, I was in Lofoten for a marvelous week of climbing. The trip was made all the more fun by the Finnish lads camped next to us on the field by the beach. They helped celebrate my 30th birthday, around a campfire there, and a fine night it was too. Anyways, it turns out one of those guys was the blogger in question. He reminded me that as Dave and I had left Lofoten, I had given him some printouts of what would eventually become the

excellent Rockfax Lofoten guide. What goes around, comes around, and a decade later I get the beta for an icefall I've not been to before in exchange. Karma, and thanks Mikko!

One slight incident of a stuck car followed by some digging/pushing; yes, Joel, "wrong type of snow" really! ;-) and we were at the crag. The sun had given way to flat greyness and a gusty wind had whipped up but the main icefall was just as fine as it looked in photos, really big by Finnish standards, giving half a rope-length of lovely ice climbing. I led a line straight up - regretting it only slightly as I had to get off one vertical section onto an uncooperative blob of a ledge with non-warmed-up arms starting to wilt. Then Joel led another line, weaving from left to right and back again, tracing the natural line of weakness up the fall. Then, with dusk beginning to gather, we both raced up the easier fall to the left of the big one. 70 odd metres, of steep, pure ice. Not bad for a lazy Saturday.

|

| Haukkavuori main fall. |

|

| The easy line |

Back in the car we drove through snow to have supper at yet another petrol station. The

Matkakeidas and its pink donuts has long been associated with the development of the nearby crag Reventeenvuori, and pictures of its food have

graced these pages before. We both went for the rather good buffet (yes, the second of the day for Joel) and hid from the weather sipping coffee and

kotikalja. Eventually, there was nothing for it but to head back out and find somewhere to camp.

We drove to Valkeala and camped in the Pyörämäki carpark. A mean wind made pitching the tents an unpleasant race against frozen fingers, our headtorches illuminating little beyond snowflakes blasted by the wind. I built a little wall of ploughed up snow lumps around the windward side of my little tent, past experience having shown winter is not really its element and the wind can drive snow under the fly and through the mesh inner. Joel retreated to bed in his more sensible for the weather Hilleberg, whilst I brewed a cup of tea and listened to the Kermode and Mayo film reviews on my iPod. I'm currently reviewing a

ridiculously fine Mountain Equipment sleeping bag for

UKclimbing.com, so despite the foul weather outside the tent, once in that I was supremely cosy and slept like a log.

Joel, being a civilised chap, had told me not to wake him too early but he needn't have worried. Having not set an alarm, and warm in a sleeping bag that must be about as good as sleeping bags get, I woke late myself. The Jetboil didn't exactly roar, despite the gas cartridge having spent the night inside the bag with me, but I made some tea, ate a sandwich and put some luke warm water in the flask for later. Joel drank some half frozen juice for his breakfast. In the grey, windy half-light of a miserable morning, finding the nearest all day petrol station buffet seemed not a bad idea, but we're made of sterner stuff, or at least like to think so. We trekked over to the cliff through the snow-caked forests. Having not visited Pyörämäki before, Joel led the main fall, climbing it smoothly and finding pliant ice. For my lead we stumbled over to what I've nicknamed the bridge climb. A huge detached boulder needs to be overcome first. Last time I did this by struggling up the offwidth formed between the boulder and the main cliff, mixed-stylee. This time crusty, cruddy ice was dripping down the boulder allowing for some precarious but easier climbing onto its top. From here more normal ice forms the 'bridge' back onto the main cliff, where the ice continues up more easily before raring up again for the last five or so metres of vertical. It's a fun climb, and a doubled 60 mtr rope only just gets you back down again, so long again by Finnish standards.

|

| Pyörämäki |

With one lead each dispatched we headed back to the car. At first the intention was lunch and warm drinks then onto another venue, but more of the grey cold day had passed than we had realised. By the time we got to the Valkeala ABC it was apparent that there really wasn't enough daylight to go on to another crag. And with that realisation I ordered a burger and Joel went over to check out what delights their lunch buffet had to offer...

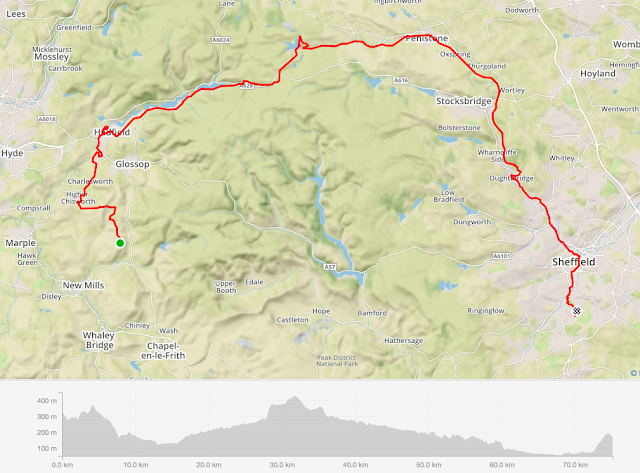

Since moving to Sheffield nearly a year ago I’ve been getting out into the Peak District and beyond quite a lot, but this has been mainly focused on climbing. I’ve ridden a lot for commuting during the week, keeping my cycling legs ‘in’ that way, but have had few opportunities for riding for pleasure. So now having finished my course, and having some time, I decided to get out and explore the Peak by bike. I didn’t want to ride on roads but I sold my trusty old mountain bike as part of our massive ‘life-streamlining’ before we moved from Helsinki. Hence I was going to need to find a route that I could do on my cyclocross bike as besides my roadie, that was the tool to hand.

Since moving to Sheffield nearly a year ago I’ve been getting out into the Peak District and beyond quite a lot, but this has been mainly focused on climbing. I’ve ridden a lot for commuting during the week, keeping my cycling legs ‘in’ that way, but have had few opportunities for riding for pleasure. So now having finished my course, and having some time, I decided to get out and explore the Peak by bike. I didn’t want to ride on roads but I sold my trusty old mountain bike as part of our massive ‘life-streamlining’ before we moved from Helsinki. Hence I was going to need to find a route that I could do on my cyclocross bike as besides my roadie, that was the tool to hand.

I started south of Chesterfield in the town of Clay Cross - my wife had to go that way for work that morning so it got me quickly away from Sheffield and towards some unfamiliar terrain. After the first 15 kms or so on quiet country lanes I dropped down into the Derwent valley just south of Matlock. Crossing the river and the Cromford Canal at High Peak Junction you get onto the High Peak Trail, and old railway line and now a national cycle route. You generally think of railways as being flat or nearly so, which makes dismantled ones such great cycle routes, but this is not the case here! The 19th century engineers needed to include massive inclines to get the railway up out of the river valley. Static locomotives were used to help trains haul or lower their loads up or down these inclines. They are not so steep as to be impossible to ride, but they are quite unlike road climbs for the cyclist: arrow straight and of a completely consistent angle, there is really nowhere to hide and no brief easings of angle as you toil up them.

I started south of Chesterfield in the town of Clay Cross - my wife had to go that way for work that morning so it got me quickly away from Sheffield and towards some unfamiliar terrain. After the first 15 kms or so on quiet country lanes I dropped down into the Derwent valley just south of Matlock. Crossing the river and the Cromford Canal at High Peak Junction you get onto the High Peak Trail, and old railway line and now a national cycle route. You generally think of railways as being flat or nearly so, which makes dismantled ones such great cycle routes, but this is not the case here! The 19th century engineers needed to include massive inclines to get the railway up out of the river valley. Static locomotives were used to help trains haul or lower their loads up or down these inclines. They are not so steep as to be impossible to ride, but they are quite unlike road climbs for the cyclist: arrow straight and of a completely consistent angle, there is really nowhere to hide and no brief easings of angle as you toil up them.

I woke up in wee small hours hearing rain on the tarp, but I stayed dry and warm under it and the morning dawned blue and cloudless. Following the Pennine Bridleway over some more hills and then plunging down towards Glossop was good riding. In Glossop, I finally left that route when it is crossed by the Trans-Pennine Trail (TPT). This long distance route goes from the Irish sea near Liverpool to North Sea at Hull, but I was about to follow it to its highest point as I crossed back from the west to the eastside of the Pennines. The route up Longdendale follows old railway track again so its very straight and smooth. The path leaves the old track where the rails used to go into the now closed Woodhead tunnel. The TPT instead crosses the busy A628 (it is busy with lots of big trucks - take care!) and goes steeply up a hillside (more pushing) before following a rough bridleway up to the top of pass. The Woodhead Pass is high and quite wild in a way, but definitely not "wilderness": a busy road goes over it, Longdendale has big pylons carrying electricity cables that then go under the pass using the old railway tunnel. There are also reservoirs and dams in the valley bottom. But looking up to the cloughs and crags on the northern edge of Bleaklow you can see the wild country.

I woke up in wee small hours hearing rain on the tarp, but I stayed dry and warm under it and the morning dawned blue and cloudless. Following the Pennine Bridleway over some more hills and then plunging down towards Glossop was good riding. In Glossop, I finally left that route when it is crossed by the Trans-Pennine Trail (TPT). This long distance route goes from the Irish sea near Liverpool to North Sea at Hull, but I was about to follow it to its highest point as I crossed back from the west to the eastside of the Pennines. The route up Longdendale follows old railway track again so its very straight and smooth. The path leaves the old track where the rails used to go into the now closed Woodhead tunnel. The TPT instead crosses the busy A628 (it is busy with lots of big trucks - take care!) and goes steeply up a hillside (more pushing) before following a rough bridleway up to the top of pass. The Woodhead Pass is high and quite wild in a way, but definitely not "wilderness": a busy road goes over it, Longdendale has big pylons carrying electricity cables that then go under the pass using the old railway tunnel. There are also reservoirs and dams in the valley bottom. But looking up to the cloughs and crags on the northern edge of Bleaklow you can see the wild country.