Buying clothes to wear for the winter mountains is an investment, winter climbing is not a cheap sport. So let’s start with the good news: modern outdoor clothing is, relatively speaking, cheap. Compared to any normal clothes you buy, the mark-up in the outdoor trade is rather small, and if you find something on a clearance rack at half price, the shop is almost certainly making next to no money on that sale. I bought my first Goretex jacket nearly 20 years ago with my savings from working the school holiday picking fruit on farms. It was about £130 and despite 19 years of inflation you can still buy a Goretex jacket for the same amount and it will work better than my 1990-vintage Phoenix Topaz. Secondly, modern outdoor clothing is really good. If you have the money to buy top of the range from any of the famous brands it is really, really, really good. But a sensibly-designed, own-brand fleece from Millets or Decathlon is going to be as good as the top of the range Berghaus or North Face fleece of twenty years ago whilst being a third of the price not even taking into account inflation. I might not go as far as to say you can’t go wrong, but like having SatNav – it’s getting ever harder to go really wrong.

Sometimes the British winter can get pretty wild - and this is just Wales! Scotland gets more knarly!

But good value is the result of

competition and this comes from a huge choice. You can hardly moan

about this, but of course this does making choosing exactly what you

want difficult. This article aims to give some basic information for

those who are new to the game, and perhaps a few alternatives

thoughts to those who aren’t.

This article, being UK Climbing, is

aimed primarily at winter climbers going to Scotland, Snowdonia or

the Lakes. Climbers often need a little extra warmth than winter hill

walkers due to pitched climbing necessitating standing still and

belaying in foul weather, although otherwise the basic philosophy is

the same.

Dry and still

Winter clothing keeps you warm by

keeping you dry and from stopping the wind. You lose heat in two

major ways – conduction and convection (forget radiation – there

ain’t much that can be done about that). Conduction is heat energy

moving (in this case away from your body) through solids and liquids.

Convection is the same but through gas – the air, moving in the

form of wind. Keeping dry is about reducing conductive heat loss. You

can stand around naked in still air at -10 and if you are dry it is

fine for a few minutes, but try getting into a lake where the water

is 5 degrees and you’ll know all about it. We do both of these

regularly in Finland, often together, so I say this from personal,

and normally quite embarrassing, experience. Just to complicate

matters, you can get wet in two ways – from the outside (snow,

sleet, rain) or from the inside (sweat); your clothes have to stop

moisture from either being near your skin. Keeping out the wind is

about avoiding heat loss through convection. Anybody who has stood

around belaying on a windy day without a windproof jacket will

understand exactly how this works.

Inside out

|

| Dry and still conditions Nordic ice climbing, a micro fleece and vest was fine even if it was -10. |

The layering principle is the standard

way to dress for the winter mountains. There are clothing systems

that claim they aren’t based on the layering principle, but due to

basic physics they are really – it’s just a different take on it:

normally combining two layers into one. It is best to think of the

layering principle from the inside out starting with the clothes

against your skin. This is the base layer – although often referred

to by your granny as thermal undies. Base layers suck the sweat away

from your skin as quickly as possible transporting it outwards to the

next layer. This is called “wicking” - probably because “sucking

up sweat” is such a horrible image. The quicker your base layer

wicks, the dryer you stay – and as we discussed above, the warmer

you will be. Next comes the mid layer – normally this means fleece

these days. The mid layer is insulation that traps air which

insulates you from the colder air outside your clothes. Your

insulation mid layer also needs to be able to transport sweat

outwards without holding the moisture. This is why it is rare to use

a down jacket as a mid-layer, feathers hold moisture so it would get

clammy from sweat and stop working well. Finally there is the shell

layer. When I started climbing everybody just called these

“waterproofs” and were done with it, but this is where things get

a bit complicated because you have in effect two types of shell –

those designed just to keep the wind out – windproofs – and those

that keep both the wind and rain out – waterproofs. If you want to

be down with the kids you can call the former softshells and the

latter hardshells, but for the moment this unnecessarily complicates

matters – so I won’t. Next we will go on to discuss the basic

options available for these layers, before heading out to the

extremities – hands, feet and head.

Base layers

Until some New Zealand sheep farmers

hit on a really great business idea a few years back, base layers

meant synthetics – mainly different types of polypro. I have

synthetic base layers made by Helly Hansen, Karrimor, Jack Wolfskin,

Berghaus, Lowe Alpine and others that I don’t recall. All work –

even my 18 year old smelly Helly that I still regularly wear whilst

cycle commuting in winter. There is not so much to distinguish them

in terms of wicking – get any polypro base layer from a decent

manufacturer and you won’t go wrong. Making sure they don’t have

seams that rub or labels that itch is probably the most important

consideration. One feature they do all share in common though is that

if I wear them for more than ten minutes, they stink under the arms

(and round your nether regions with the long johns). Different firms

have claimed to have solved this issue over the years but none I have

tried have succeeded. It seems that most blokes at least will make

synthetic base layers stink. This is where we get back to those

enterprising antipodeans. I reckon Merino wool is a real revolution

in thermal undies. It still wicks to my mind as well as synthetics

(others disagree on this but they seem to be a minority) but it is

really quite spookily smell resistant. I can wear a cotton t-shirt

for a day without it getting whiffy, but after two days it's not so

great. I wore my favourite merino baselayer for four days ice

climbing last Easter in Norway – and no hint of smell. To me this

is amazing and in my experience the only downside to merino is that

it tends to cost more and the material is a bit delicate in

comparison to synthetics.

Mid Layers

Fleeces are pretty simple things –

fluffy polyester knits that trap warm air and thus insulates you –

but they come in bewildering range of styles and types. The fluffier

or thicker it is, the more insulation that garment will offer. For

climbing, simple and fitted is best. As increasingly with modern

clothing systems we add insulation to the outer layer – the belay

jacket idea (see below) - micro fleeces are amongst the best mid

layer garments. They offer a fair amount of warmth but aren’t bulky

and as shell layers become ever better cut and fitted, this is

important. Hi-loft fleece is the fluffy type that makes you look like

a brightly coloured sheep but is superb in cold conditions. They are

far, far lighter than old heavy weight fleeces and compress well.

They also make ace pillows once you are in the tent at the end of day

– but many might find them too warm under a shell if climbing hard

or moving fast. If you are sure you are going to be wearing your

mid-layer all day, as most people will for winter climbing, consider

a pullover rather than a jacket version: lighter, no annoying zip

lower down near your harness and, best of all, normally cheaper.

Mid-layer for your legs is more complex

because legs generally need less insulation so many find that if

their leg wear has some wind resistance to it, it will actually be

their outer layer for much of the time. Softshell trousers made out

of a stretchy, breathable and wind-resistant material have become the

legwear of choice for many winter climbers in recent years, but

summer trekking trousers over long johns can also work well. But even

the expensive Schoeller materials are not completely windproof

(unless they are the expensive and less breathable membrane type) and

in cold temps or when static for long periods I’ve found them to be

not warm enough. This when you might have add some sort of shell over

them, or pick a more specialist pair of trousers that are insulated

in some way.

Windproofs

|

| My great Marmot windproof on the top of a cold but (for once!) dry Scottish mountain. |

|

| A Rab windproof - super breathable for big ice pitch I'm about to try, Norway. |

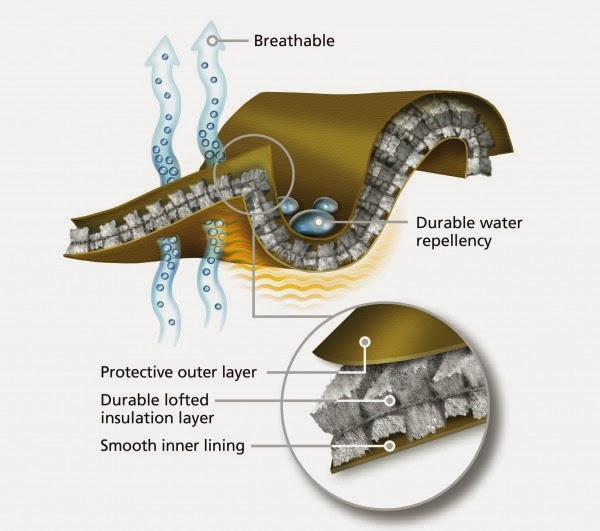

Waterproofs

Making a waterproof jacket is easy –

the trick is to make it waterproof in only one direction. As you do

any exercise you sweat. If this sweat can’t escape through your

waterproof layer, it will wet your mid and base layers just like rain

or melted snow from outside would do. Conducted heat loss then begins

and you get cold. This is why your waterproof jacket also need to be

breathable. Breathable simply means that the jacket material in some

way to do with it physical structure or chemical make-up allows

moisture vapour (sweat) through from the inside to the outside, but

does not let liquid water (rain) in from the outside to inside.

Materials are getting better – the

Goretex of today breathes more readily than the Goretex of the jacket

I bought in 1990 and there are now many competitor fabrics that seem

to work adequately and particularly with eVent there is now a fabric

that many believe is better than Goretex. But just as importantly is

that designs have improved massively in the last decade. Designers

are making jackets that are slimmer fitting, tailored to the needs of

climbers or hikers, and use cleverer technologies like thin seam tape

or bonding technologies that allow the material to breath better all

over. In the early 90s I became a huge fan of Buffalo clothing

because it meant I didn’t need my Goretex jacket for winter

climbing and that meant getting less clammy and cold from sweat

despite not being waterproof. I still won’t wear a Goretex for,

say, skinning uphill whilst ski mountaineering, but my Arctryx

paclite Goretex I can wear happily when ice climbing on drippy days,

or hiking in sleety weather, without getting sweaty inside. It’s

just a better designed coat made out of better material than the

early 90s shells – and the fabrics of today are further improved

than the six year old goretex of my Arctryx.

For the British mountains in winter,

what you will want though is a shell jacket with a good hood - the

best tend to have a wire in them to create a peak, and the hood needs

to be big enough to go over a climbing helmet. Unsurprisingly,

British companies (Berghaus, Mountain Equipment, Montane etc.) often

have the best hoods for full on conditions – putting more emphasis

on protection than peripheral vision. Some US firms have even made

jackets designed specifically for the British market including bigger

than normal hoods – showing the difference in design philosophy.

More and more shells now use waterproof (water resistant some say)

zips. These save weight, but some still prefer their winter jacket to

have a storm flap that covers the zip for maximum protection.

Booster Layers

Booster layers – often called belay

jackets – are insulated coats that you stick on over your shell

(windproof or waterproof) when static or just really cold.

Traditionally these were down filled, although down doesn’t mix

with rain or wet snow well, so increasingly many climbers are going

for modern synthetic fills such as primaloft. These keep their

insulation value better if getting damp, but down is lighter, packs

down smaller and last much longer if well looked after. See my

earlier

article on belay jackets for much more on this.

Alternative systems

For a long time the most famous

‘alternative systems’ in the UK to the layering principles

outlined above were Buffalo and Paramo. You can read much more about

both on their websites, but both avoided membrane waterproof fabrics

like Goretex. What they lose in waterproofing they gain in

breathability. The fans of both systems often have a slightly zealous

air to them that come with having ‘seen the light’. I should

know: in the mid-90s I was a hardcore Buffalo boy. I was living in

Scotland and working in shop that stocked the system felt the urge to

try and convert the Goretex clad infidels to the true and righteous

(and slightly odd looking) path. I’ve never used Paramo, so their

crusaders will have to speak up in its favour but back then Buffalo

was without any doubt the best value for money mountain clothing

system you could buy. Montane also make pertex and fibre pile

products very similar to Buffalo. Pertex and fibre pile is not always

perfect, but for serious winter climbing when on a budget it is still

well worth looking at. Stephen Reed, owner of Needlesports has an

excellent

manifesto for the Buffalo system.

Feet, hands and heads

Keeping your extremities warm is one of

the hardest parts of choosing your clothing system and my experience

is that in particular finding the right glove system is an annoyingly

expensive experience of trial and error. Hopefully some of

Feet

What boots you wear is dependent on

what you are doing - winter hill walking, mountaineering and easy

climbs, mid grade pitched climbing, or hard climbing. For hill

walking and easier routes many will wear a B2 (link) rated boot -

with a bit of flex to them and not too heavy. These can be super

traditional leather walking boots, or more modern styles made with

various synthetic materials. Boots for climbing in tend to be rigid -

B3 rated for prolonged crampon use and built with warmth in mind.

Boots for the hardest climbs are rigid but lighter, possibly

sacrificing some warmth and support but anyone interested in those

type of boots won't need this article. Opinions vary on what to wear

inside. When I started climbing in Scotland in the early 1990s

everyone wore plastic boots, and most people seemed to use inside a

liner sock under a woolly sock. You didn't need to worry much about

cold feet with that combo but it compromised climbing (and walking)

performance. With better fitting leather boots wearing one pair of

medium to thick socks inside seems to make more sense to make the

most of the fit and climbing performance of your boots. Good mountain

socks from manufacturers like Extremities, Thorlo, Smartwool,

Bridgedale and the like are very nice but do seem horribly expensive

for a pair of socks. I found that high wool content socks - normally

sold as hiking socks - from even Tesco can do the job fine. My two

pairs of Tesco hiking socks cost about seven quid but have kept my

feet nice and warm inside my Nepal Extremes even when ice climbing in

the bitter cold of the Norwegian arctic. The old Extremities mountain

socks I have are a little warmer, but at something like eight times

the price!

For UK mountains, I still think that

gaiters are pretty vital. If you get water or mud over the top of

your boots, you will get cold feet once above the snowline. The

gaiters that come attached to many shell trousers might do a good job

at keeping snow out of your boots, but not the boot sucking mud of

many a British walk-in. Good gaiters are nice, but cheaper ones do

the job well enough. Look for a pair with a front zip, these are much

less hassle if you need to tighten your laces than the back zip

models. Places like Decathlon do some very good value pairs with

decent technical designs. Full foot gaiters like Yetis are great for

keeping snow out of your boots on prolonged trips where you are

camping in deep snow, but in my experience are a bit over-kill for

day climbs. They do make boots slightly warmer by keeping snow off

your boots and laces - but the majority of heat-loss from the feet is

through the soles of your boots, so Yetis aren't the magic bullet to

warmer feet that some people expect.

Hands

Glove and mitts are notoriously

difficult to get right and, due to the complexity of the stitching

and taping, expensive as well. Most winter climbers find a system

that works for them after years of trial and error. Mitts are warm

and often waterproof but most find them hard to do anything technical

in. Softshell gloves are light and dexterous - picking the no. 3 wire

of your racking krab is easy enough - but you quickly get cold

fingers when belaying and water goes straight through them. Goretex

or eVent mountain gloves are somewhere in between - a bit warmer and

you can use your belay plate, but you might drop that wire. In my

experience you need more dexterous gloves for Scottish climbing,

particularly mixed routes where the majority of pro is rock gear.

Softshell, or some other thinner types of gloves work well, with

mitts for belays and the walk down. For pure icefalls, goretex (or

similar) gloves work well - ice screws aren't too fiddly to use with

them and they are warmer. Ice climbing in Scandinavia I have often

just used my mountain gloves all day, for climbing, belaying and the

descent, but for hiking up to Scottish climbs, takes something thin

and stretchy for the approach; any old gloves will work fine

including woolly ones, keep your main gloves dry and ready for the

actual climbing. Finally, take some light, insulated mitts for

belays, descents in horrible weather and for simply when your hands

get really cold. Buffalo mitts remain a favourite, very light and

pretty cheap, but if you think you might be wearing them to belay

much get something with reinforcement on the palms. Dachstein mitts

deserve a special mention as many and will go on at great (boring?)

length about how they are the be all and end all of Scottish winter

handwear. I'm unconvinced myself, finding them heavy, stiff and

neither particularly grippy or warm - but a thousand happy punters

can't be completely wrong so it may be worth trying them out.

Some specific recommendations: my

current softshell gloves are by Ortovox - I got them mainly because I

couldn't afford the Black Diamond Dry Tool gloves and they were the

only other ones my local shop had, but they have turned out to be

hard wearing, being three seasons old and surprisingly warm. If the

price of softshell gloves puts you off, try Extremities Sticky

Thickies over a pair of thinnies (or even cheaper no-brand 'magic'

gloves) as a cheaper and surprisingly warm alternative. I used this

system for a few seasons of regular Scottish routes and it worked

great for me for more technical mixed routes where you are mainly

placing nuts and cams. When it comes to a more general, waterproof,

mountain glove; for about six years I used a pair of Goretex gauntlet

gloves made by Mountain Hardware. These were absolutely superb: the

palms and fingers were made with sticky and absolutely bomb-proof

rubbery material that no number of abseils could wear out. They had

minimal insulation, just a light brushed lining to protect the

Goretex, but this meant they were very dextrerous and, for all but

the most technical of routes, you could put them on and just keep

them on all day. Of course they seem to have stopped making that

model now, which all too often happens with a brilliant product! I

replaced them last year with Rab Makalus - decent gloves but with

some insulation making them less dexterous than the Mountain Hardware

ones, and with a less good cuff arrangement. The eVent does seem very

good though. If buying waterproof climbing gloves one really

important thing is get them to fit your finger length; any floppy

bits at the ends of the fingers seems to be magically attractive to

the gates of any karabiner you are trying to handle - not what you

want whilst desperately trying to get a quickdraw onto your ice

screw. For mitts, bargain bins in climbing shops in the summer or

somewhere like Decathlon have proven good bets for me in the past -

any loose fitting nylon-covered and pile-lined mitts should be pretty

warm. My current favourite belay mitts are Extremities and were

bought in TKMaxx for about a tenner.

Heads

For ultimate warmth and protection you

want a balaclava - I like light and stretchy ones because I tend to

carry it much more than I wear it, plus with a black powerstretch

balaclava you are also always ready to attend fancy dress parties as

a ninja. Back out on the hill, wearing a hat and some sort of fleecy

neck tube is far less likely to get you arrested as a bank robber and

is more flexible an arrangement. And remember: bobble hats both look

ridiculous and don't fit well under climbing helmets, so buy a good

looking beanie and you can also use it for bouldering, as long as you

remember to take your top of first.