|

| 4 am, somewhere in South Yorkshire - yes that's what getting up after 3.5 hours sleep feels like. |

Moving from Finland back to the UK after many years was a surprisingly un-traumatic, if rather expensive, experience but I knew that I really would miss the ice climbing. Of course, there are other things I miss too but for this post we'll stick with the ice climbing. On the other side of the scales to lack of ice climbing was the opportunity to do more winter mountaineering, in Scotland or at least in Wales or the Lake District. Unfortunately work and family commitments have made this more difficult than I hoped; besides anything it's three hours driving to get the Lakes or Snowdonia and the Highlands are considerably more. Hence, since winter has at least fleetingly visited the more southern hills of the British Isles, I had only managed one visit to the Lake District this winter; a good day out in the hills with good company, but disappointing from a climbing point of view as even on one of the highest crags in the region the turf wasn't frozen* under the snow and we 'scrambled' the route with boots and gloves; no need for ice tools or crampons.

|

| Phone snaps: a better topo in from an old guide/a snowy Lake District/a happy climber |

Over the last week the forecasts had suggested that winter climbing conditions might be forming again south of Hadrian's Wall and I was really keen to get out. Friday was going to be the only day I could manage it, but even then I needed to be back not long after the kids got home from school in order to look after them. I figured I could drive to either the Lakes or Wales late night Thursday, sleep in the car for a bit and get an early start - but what would be in condition that I could comfortably solo? I kept checking the forecasts and conditions reports Thursday evening looking for info as to something being 'in', but it really wasn't clear. Eventually I decided I'd risk the Lake District, but sleep at home and leave very early. I packed my kit, made lots of thermos flasks of hot drinks, sandwiches and put 'breakfast' in a bag by the front door. I'm not good at going to sleep early so it was about midnight when I did - early for me. I didn't even need the alarm, as I woke up at 0355. Having been organised with packing the night before, I just put on my clothes, cleaned my teeth, and was in the car driving at 0409.

|

| Avalanche debris, some hundreds of metres belows the cliffs. Yes, you can big avalanches in England! |

Sheffield was quiet, taxis moving not much else. The moors even quieter, up over Snake Pass - a careful eye on the car thermometer, conscious of not having winter tyres like in Finland, but the temperature never hit zero even on the top of the pass as the lights of Manchester spread out below. Down around Manc and up to the M6, there's more traffic - lots of trucks on early runs - but its smooth going through the dark. Into the Lakes, the GPS takes me on little road I've not driven before missing Windermere and coming out halfway up the Kirkstone Pass. It is snowing on the pass, but the road is still wet and not slippery. Down in Patterdale I park, gear up and walk up the road. It's not quite 0730 yet and still dark enough that I need my headtorch on to see the map. Heavy wet flakes being driven by the wind as I walk up the sodden track along Grisedale. It doesn't feel good for winter climbing but I can see lots of snow higher up. I've not climbed on St Sunday Crag before so need to check the guide to work out where I'm meant to head. It's quite impressive from below, there's 300 mtrs or so of ascent up a steep hillside to get to the lowest rocks then another couple hundred to the summit ridge. I slog up the hillside through a gather blizzard, listening to Melvyn Bragg's proud Cumbrian tones as I do via a podcast - fitting really. It's pathless and brutal, but I gain height quickly to where the steepness eases off a little before the cliffs begin. St Sunday is seamed with gullies and I can see the one to right of Pinnacle Ridge, my target, has spewed out a chunky, heavy avalanche - the debris coming several hundred metres down the hillside below the gully's mouth. I could see this was sometime ago, and the debris now provide a hard and fast route up to the start of the ridge once I clip my crampons on.

The ridge itself was a delight, never desperate, but plenty of opportunities to get my head back into British mixed; hooking, torquing, swinging tools into frozen turf. The crux is no pushover - and I chimney up carefully, double checking my hooks - well aware I'm alone and not on a rope. Having been soloing a lot easy grit routes recently, I even chuck in a gloved handjam on the crack, preferring that to a tenuous torque.

|

| Looking back down the crux corner |

|

| The final pinnacle of Pinnacle Ridge, II. Grisedale is below. |

The route is decent length too, meaning lots of enjoyable climbing. Hard snow above the ridge's terminus leads on to the summit plateau - the weather has improved and there are great views all around. Helvellyn's highest corries are still hidden in clouds, but the views down to Ullswater and over towards High Street are fantastic.

|

| Looking down towards Ullswater. |

It's only mid-morning, so although I know I can't stay all day, I still have time. The hard snow on the headwall suggests the gully to right of the ridge might be a quick was back down, and so it turns out to be. I quickly down climb it predominantly on hard, secure neve. I traverse along the base of the cliff to East Chockstone Gully, reputedly the best of the cliffs gullies. It's meant to be just I/II but there's a distinct ice pitch today in the bottom narrows.

|

| A bit steeper than your normal grade I gully! |

I climb up to that and start climbing the maybe 8 metres of almost vertical ice. It looks impressive but ice is very soft. By bridging one foot across to rock on the other side of the narrows I climb most of it but its that 3D chess thing: continually spread your weight and never committing to just one foot hold or tool placement, I get both tools in the ice above the steep section, but its too soft for me commit to swinging all my weight over onto the ice. Waves of spindrift pour down the gully and over me to just to complete that full-on feeling. So not today and not soloing; I gingerly down climb back into the welcoming snow of the gully bed. I try forcing a way around the narrows on vegetated mixed ground to its side, but it is steep and the thick heather and reed grass is not properly frozen under the heavy snow. It seems silly, so I back down and out of the gully. Traversing further along, I come to the next clearly defined gully, Pillar Gully. This has firm neve in it and I can see no nasty surprises looking up, so I take it, trying to do my

best Ueli Steck impression to the top. It's a pretty poor impression to be honest, with a few sneaky, panting rests, but the gully is very straight forward, I even catch myself looking down it and thinking "I could ski this with a bit more snow in it" but enough of such silly thoughts. With good hard snow the whole way, soon I'm back out again on the snow blasted summit.

I slog to St Sunday's highest point, put on a duvet to ward off the maelstrom, check the compass and map and head east and down. The walk along the ridge is lovely as soon as I'm down below the cloud. The heavy snow that has been blasting past me on the cliff has whitened everything below, right down to the lake.

|

| Walking down and towards the sunshine |

Back down on the valley floor, the new snow is melting into already sodden ground and water is streaming everywhere. I walk back down to Patterdale admiring the fast flowing Grisedale beck roaring down below the track. I'm back at the car, changed and driving south by 1330, with only the traffic around Manchester to worry about.

|

| Red Screes gone white. |

|

| Looking down from the Kirstone Pass towards Windermere. |

|

| Back over the Snake Pass, not too far from home now. |

*For non-British winter climbers, the ethics of winter climbing here can seem a bit arcane, but are actually deeply-rooted and come about both from sporting reasons (routes should be harder as winter ascents than in summer!) and increasingly environmental reasons (frozen turf is good to climb on and seems not bothered by being wacked by the ice tools of passing climbers. Unfrozen turf rips up and off the cliff, and the habitat of rare alpine plants can be destroyed).

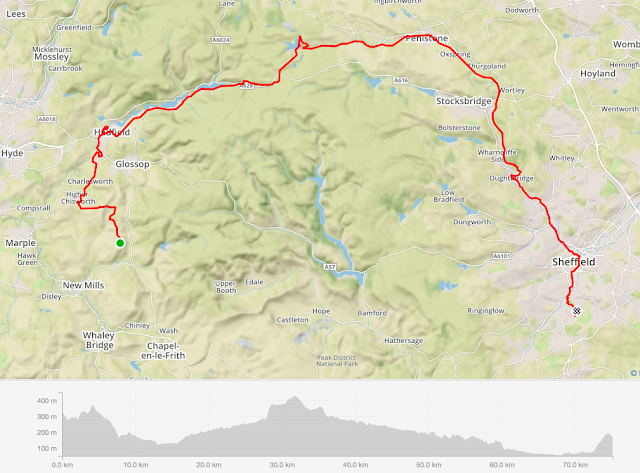

I've spent a fair bit of time at Stanage over

the last year; I was always a bit sniffy about gritstone previously. Not that

there is anything particularly wrong with it, but there are lots of British

(well, English) climbers who don't seem to see much past it. Grit climbing is

great, but if you start your climbing in a non-gritty area of the UK, you can

see there are lots of other types of British rock and British climbing. Yet,

for Sheffield residents it IS just very convenient. 20, 25 minutes in the car

and you have thousands of routes, at all grades, many with real historical

resonance too. And so I've been going lots, and as a result getting lots of

routes climbed. Of all the grit crags, Stanage is the most impressive. It is so

popular and well known, it's almost a cliche; but when you stand on the top of

cliffs at "Popular End" and watching the edge sweep away northwards -

about 6 kms, not unbroken but pretty consistent cliffs along that stretch - it

really is one of the most impressive sights in England. But it is not the Alps though, or the high

mountains of the Norwegian Arctic. Few of Stanage's rock climbs reach 20 mtrs

in height. If you want to have a BIG day out climbing, you are going to have to

climb a LOT of routes.

I've spent a fair bit of time at Stanage over

the last year; I was always a bit sniffy about gritstone previously. Not that

there is anything particularly wrong with it, but there are lots of British

(well, English) climbers who don't seem to see much past it. Grit climbing is

great, but if you start your climbing in a non-gritty area of the UK, you can

see there are lots of other types of British rock and British climbing. Yet,

for Sheffield residents it IS just very convenient. 20, 25 minutes in the car

and you have thousands of routes, at all grades, many with real historical

resonance too. And so I've been going lots, and as a result getting lots of

routes climbed. Of all the grit crags, Stanage is the most impressive. It is so

popular and well known, it's almost a cliche; but when you stand on the top of

cliffs at "Popular End" and watching the edge sweep away northwards -

about 6 kms, not unbroken but pretty consistent cliffs along that stretch - it

really is one of the most impressive sights in England. But it is not the Alps though, or the high

mountains of the Norwegian Arctic. Few of Stanage's rock climbs reach 20 mtrs

in height. If you want to have a BIG day out climbing, you are going to have to

climb a LOT of routes.